Author: Margaret Norman, Director of the Jewish Community Relations Council in Birmingham

A 2015 piece published online in Time, days after the tragic shooting at Mother Emmanuel AME Church, opens: “Think of the Civil Rights Movement, and you’re unlikely to think of Charleston, SC.”[1] Yet, as the same piece rightly points out, Charleston did have a movement and that movement featured many of the same types of events as elsewhere that have been cemented into our collective memory of the struggles for civil rights: sit-ins and boycotts, school desegregation and labor strikes. It’s, likewise, true that Charleston does not “rise to the top of discussions” in the same way as Greensboro, Selma, or Birmingham.[2]

I was curious when I visited the College of Charleston as a Pearlstine/Lipov Research Fellow in 2023 to learn not only how Charleston’s Jewish community reacted to civil rights events of the 1950s and 1960s, but how their actions may have differed from a Jewish community in a city like Birmingham—where I’d been working since 2020—which is broadly recognized for its role in civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. I was interested in how these two communities recalled and remembered their roles within this pivotal historic moment, and the prominence of those memories in each community’s contemporary identity.

I was curious when I visited the College of Charleston as a Pearlstine/Lipov Research Fellow in 2023 to learn not only how Charleston’s Jewish community reacted to civil rights events of the 1950s and 1960s, but how their actions may have differed from a Jewish community in a city like Birmingham—where I’d been working since 2020—which is broadly recognized for its role in civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. I was interested in how these two communities recalled and remembered their roles within this pivotal historic moment, and the prominence of those memories in each community’s contemporary identity.

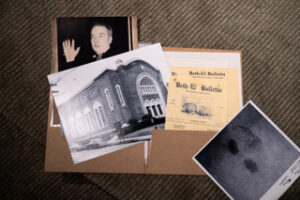

In Birmingham, I’ve spent the last four years with a dedicated team developing the Beth El Civil Rights Experience (BCRE), a project exploring the intersection of Birmingham’s Jewish and civil rights histories. What’s most remarkable about this project to me is the will and desire that propelled it into being. The BCRE explores this history in all its complexity—both Jewish action and inaction—which grew from a longstanding desire of the congregation and was supported by tremendous grassroots efforts. In Birmingham, a city undeniably known for its civil rights history, to engage with this history is a necessity.

In Birmingham, I’ve spent the last four years with a dedicated team developing the Beth El Civil Rights Experience (BCRE), a project exploring the intersection of Birmingham’s Jewish and civil rights histories. What’s most remarkable about this project to me is the will and desire that propelled it into being. The BCRE explores this history in all its complexity—both Jewish action and inaction—which grew from a longstanding desire of the congregation and was supported by tremendous grassroots efforts. In Birmingham, a city undeniably known for its civil rights history, to engage with this history is a necessity.

My time in the archives at College of Charleston yielded several insights, the first of which being, quite simply, that Jews who lived in the city in the 1950s and 1960s were navigating many of the same challenges and tensions as their Deep South neighbors. In an oral history with Rabbi Gerald Wolpe, originally of Roxbury, Massachusetts, who led the Conservative Temple Emanu-El until 1958, he describes how “the whole segregation and integration issue was red hot.” He elaborates:

My time in the archives at College of Charleston yielded several insights, the first of which being, quite simply, that Jews who lived in the city in the 1950s and 1960s were navigating many of the same challenges and tensions as their Deep South neighbors. In an oral history with Rabbi Gerald Wolpe, originally of Roxbury, Massachusetts, who led the Conservative Temple Emanu-El until 1958, he describes how “the whole segregation and integration issue was red hot.” He elaborates:

When I preached a sermon, I had to think very carefully about trigger words. The Jewish community was vulnerable at that point. It was small. On one side, the black community was threatening to boycott Jewish stores if they didn’t take this position yet, on the other hand, white citizen groups were saying, “Hey, wait a minute, you’ve been here five generations. How come you don’t think the same way as we do?”[3]

As in Birmingham, mid-century Jews in Charleston occupied an uncertain place in the Southern racial hierarchy, experiencing both the privileges of whiteness and exclusions predicated on difference. Birmingham’s Temple Beth El was the site of an attempted bombing in 1958 that both exposed the congregation’s vulnerability and highlighted their relatively privileged status, as evidenced by the support of white interfaith partners and local law enforcement.

As in Birmingham, mid-century Jews in Charleston occupied an uncertain place in the Southern racial hierarchy, experiencing both the privileges of whiteness and exclusions predicated on difference. Birmingham’s Temple Beth El was the site of an attempted bombing in 1958 that both exposed the congregation’s vulnerability and highlighted their relatively privileged status, as evidenced by the support of white interfaith partners and local law enforcement.

Rabbi Burton Padoll, the outspoken spiritual leader of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (KKBE) from 1962-1968, describes the reticence, particularly of Jewish merchants, to stir up trouble when they had faced relatively little “open antisemitism in all the years of what went on in Charleston.”[4] Padoll came to his southern pulpit with the goal of making a difference in the realm of civil rights, but struggled with a congregation that wasn’t always pleased by his vocalness on these issues. This was a dynamic I certainly recognized from tensions in Birmingham between those who wanted to act publicly and those who felt Jews should be enacting change from behind the scenes, lest they invite antisemitic backlash from the community.

One question I had going into my research fellowship was to what degree Jewish communities were in conversation with one another during this time. The Jewish community in Charleston certainly would have been aware of the bombings and attempted bombings that impacted Jewish communities throughout the South in the late 1950s. I was particularly curious to explore the papers of Charleston’s Jewish Community Relations Council, and within these files I did find a report from 1959 on “Recent Desecrations of Synagogues and Other Anti-Semitic Attacks.”[5] In minutes from a meeting on March 21, 1960, it’s written:

Another thought was that we might discuss some of the problems which were faced by our sister communities within the South so that if such a situation would occur in Charleston we would have some sort of history to go by.[6]

Minutes from October 30, 1961, recap a meeting where a Mr. Moseson, from the Savannah Jewish Community Relations Council, addresses the King Street merchants in Charleston;Charleston, briefing them on boycotts in his home city. Intriguing to me, notes from spring of 1963 include nothing of the events in Birmingham; a noticeable void. As I continued to dig through notes, I saw the Charleston JCRC addressing local instances of antisemitism occurring throughout this pivotal decade, such as the exclusion of local Jewish students from the Ashley Hall school.

Why did Charleston’s civil rights movement never accrue the level of attention of Birmingham’s? And how did the relative quiet of those years (relative to a city like Birmingham, which splashed across national and international news waves), impact its stature in local memory today? These were some of the questions that rolled through my head as I explored the city, between the archive and several sites of historical preservation.

A vital factor in both the drama and success of Birmingham’s local movement was the cultivation of “creative tension” by its brilliant leaders. This dynamic was made possible by the level of open violence in Birmingham, both sanctioned vigilante violence and on behalf of local law enforcement. In Charleston, I heard again and again about the subdued reaction of local law enforcement to the civil rights conflict, and about the legacy of a polite society where discrimination was more subdued than in industrial Birmingham.

But Charleston also grapples with a history that Birmingham, as a post-Civil War city, often doesn’t–that of slavery. Birmingham, of course, has been impacted by the legacy of slavery. Consider the migration of formerly enslaved people to the city to work in the mines, either voluntarily, or as forced convict labor. But just as Charleston has begun to address this part of its past over that of the civil rights movement, Birmingham has done the reverse. During my time in Charleston, I visited the excellent and creative Aiken-Rhett House. I noted the ways that the history of slavery marks the public landscape, as the legacy of civil rights does in Birmingham, with markers and plaques. And on a tour of the historic Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, I saw how that congregation has grappled with the history of Confederate Jews and the enslaved labor that went into the very construction of their historic building. As our guide explained in words that echo what we tell guests who visit the Beth El Civil Rights Experience, “We have to understand our past to be better moving forward.”

[1] Joiner, Lottie, Charleston’s Place in the Civil Rights Movement, June 19, 2015 Time, https://time.com/3928713/charleston-civil-rights-movement/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Wolpe, Gerald, 1927-2009. “Jewish Heritage Collection: Oral history interview with Gerald Wolpe” Lowcountry Digital Library, College of Charleston Libraries, 11/15/1999.

[4] Padoll, Burton, 1929-2004. “Jewish Heritage Collection: Oral history interview with Burton Padoll” Lowcountry Digital Library, College of Charleston Libraries, 10/21/1999.

[5] Recent Desecrations of Synagogues and Other Anti-Semitic Attacks, memo from Federation and Welfare Fund Executives to Isaiah M. Minkoff, January 5, 1959. Charleston Community Relations Committee papers (Box 1, Folder 1), College of Charleston Libraries, Charleston, SC, USA.

[6] Minutes, March 21, 1960. Charleston Community Relations Committee papers (Box 2, Folder 5), College of Charleston Libraries, Charleston, SC, USA.

Leave A Comment